On This Day in 1996, The US Olympic Soccer Team's Quest for History on Home Soil Ended in a Group Stage Exit

The parallels were impossible to ignore. Sixteen years after Herb Brooks led a collection of college hockey players to Olympic gold against impossible odds, another American team prepared to chase their own miracle. This time, the dream was simply advancing past the first round—something no U.S. Olympic soccer team had ever accomplished.

Bruce Arena surveyed his squad in the summer of 1996 with the kind of cautious optimism that comes from understanding both potential and reality. Like Brooks' 1980 hockey heroes, Arena's team was built around fresh-faced collegians who would face seasoned professionals from around the world. The coach had assembled a roster anchored by three over-23 players—defender Alexi Lalas, midfielder Claudio Reyna, and goalkeeper Kasey Keller—who carried the bulk of international experience. At the same time, the remainder consisted of talented but largely untested youngsters.

"Something good will happen early for us. We will have 82,000 people cheering for us," Arena declared before the tournament opener against Argentina. The home field advantage represented their greatest asset in Group A, where they would face medal favorites Argentina, an improving Tunisia side, and a Portuguese team brimming with young professional talent. Media expectations remained predictably low. Arena understood the challenge ahead: in its ten previous Olympic appearances, American soccer had never advanced past the opening round.

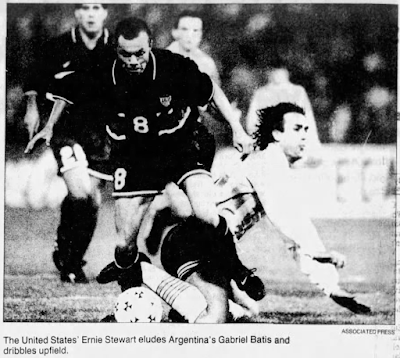

Argentina arrived in Birmingham as co-favorites alongside Brazil, boasting a squad that included future stars like Diego Simeone and Hernán Crespo. For Arena, the July 20 opener at Legion Field represented both opportunity and a measuring stick. A sellout crowd of over 80,000 would provide unprecedented support, but Arena knew crowd noise alone couldn't bridge the technical gap his team faced. The Americans began brilliantly. Just 28 seconds after kickoff, Reyna trapped a pass from Imad Baba and buried it into the corner for a stunning 1-0 lead. Legion Field erupted as the crowd dared to dream of an upset. For thirty minutes, the Americans matched Argentina's pace and precision, suggesting that this collection of college players and MLS newcomers belonged on the same field as South America's finest.

"That lifted us, really, for the first half-hour," Reyna reflected later. "It's also difficult when you score that early, because you have 89 more minutes against a super team."

The moment of truth came in the 27th minute when Argentina's experience began to tell. A brilliant crossing pass found Claudio López, who converted to level the score and deflate American hopes. The second half belonged entirely to the visitors, as Crespo's sliding finish in the 56th minute and Simeone's late strike sealed a 3-1 defeat that felt both closer and more distant than the scoreline suggested. The loss left Arena's team needing results against Tunisia and Portugal to advance. Tunisia, missing key players through injury and suspension, presented the Americans with their most straightforward path to a vital three points.

On July 22, before a reduced but still substantial crowd of 45,687, the Americans approached their second group match, knowing that anything less than a victory would likely end their Olympic dreams. This time, there would be no early drama. The Americans controlled the tempo from the opening whistle, with Reyna again testing the opposition goalkeeper within the first five minutes. The breakthrough came in the 38th minute through Jovan Kirovski, whose perfectly struck free kick from 20 yards sailed over the defensive wall and past goalkeeper Chokri El Ouaer.

"Jovan practices that free kick probably for 10 minutes every day after practice," Arena noted. "If he got it on goal, it was in. We've seen him do it plenty of times."

The goal originated from Miles Joseph's persistent dribbling through the Tunisian defense, earning the crucial free kick just outside the penalty area. Joseph, starting in place of A.J. Wood, exemplified the American approach—direct, physical, and unrelenting in pursuit of goal-scoring opportunities. Tunisia's task became impossible when they were reduced to nine men in the final stages. First, Ferid Chouchane received his second yellow card in the 67th minute, though referee Hugh Dallas initially failed to issue the required red card until prompted by the U.S. coaching staff two minutes later. Then Tarek Ben Chrouda joined his teammate in the locker room after picking up his second booking, leaving Tunisia hopelessly outnumbered.

Brian Maisonneuve provided the insurance goal in the 90th minute, heading home from a Lalas cross to secure a 2-0 victory. The result kept American hopes alive, although Tunisia's coach, Henri Kasperczak, lodged an official protest over the referee's handling of Chouchane's ejection. This complaint would ultimately be dismissed by FIFA.

"Now our destiny is in our hands," Arena declared, understanding that a victory over Portugal in Washington would guarantee passage to the quarterfinals for the first time in U.S. Olympic history.

The final group match at RFK Stadium on July 24 carried the weight of American soccer history. Portugal arrived needing only a draw to advance, while the Americans required a victory. Before a record crowd of 58,012, the tactical chess match unfolded exactly as Arena had predicted—Portugal content to defend their advantage. At the same time, the Americans pressed desperately for the breakthrough that would rewrite the record books. Paulo Alves provided Portugal's crucial goal in the 33rd minute, running through the heart of the American defense with the kind of clinical finishing that separated professional experience from collegiate promise. The Americans responded with wave after wave of attacks, creating numerous opportunities but lacking the final touch needed to convert pressure into goals.

The equalizer finally arrived in the 75th minute when A.J. Wood found Brian Maisonneuve for a header that sent RFK Stadium into delirium. Chants of "U-S-A!" echoed around the stadium as the Americans pushed frantically for a winner. The clearest chance fell to Reyna in the 61st minute, positioned directly in front of goal with only the goalkeeper to beat, but Kirovski's perfect cross somehow eluded the midfielder's touch. The 1-1 draw meant elimination once again. Argentina's simultaneous tie with Tunisia confirmed Portugal's advancement alongside the South Americans, leaving the United States with the familiar disappointment of first-round elimination. Eleven Olympic tournaments, eleven first-round exits—the streak remained intact.

Yet Arena found reasons for optimism in what others might view as failure. His young team had competed credibly against world-class opposition, gaining invaluable experience that would serve American soccer well in future competitions. The 1996 Olympics had ended in familiar disappointment, but they had also revealed the growing depth and ambition of American soccer. While they fell short of their ultimate goal, they had moved American soccer another step closer to the breakthrough that seemed increasingly inevitable.

The quest for Olympic soccer history would continue, but the summer of 1996 had proven that American players belonged on the world's biggest stages. Sometimes, the most important victories are the ones that prepare you for the battles yet to come.

.jpeg)