On This Day in 1995, the U.S. Shocked Argentina in Emphatic Fashion to Reach the Copa América Quarterfinals

The delight from victory over Chile had evaporated into the humid Uruguayan night just forty-eight hours later, replaced by the familiar sting of disappointment that had long haunted American soccer. Marco Etcheverry's 24th-minute goal for Bolivia had shattered the confidence that Steve Sampson's team had built through their historic win over Chile, leaving the United States facing elimination from Copa América 1995 with a whimper rather than the statement they had hoped to make.

The 1-0 defeat to Bolivia exposed the fragility that still lurked beneath American soccer's newfound attacking philosophy. Etcheverry, the Bolivian playmaker, had embarrassed Alexi Lalas with a sequence of skill that belonged in South American football's highlight reels—receiving Luis Cristaldo's pass at the top of the box, dribbling past the American defender before beating Brad Friedel with clinical precision. For the United States, it represented everything their program still lacked: composure under pressure, individual brilliance in crucial moments, and the tactical sophistication that separates pretenders from genuine contenders.

Argentina presented a challenge that bordered on the impossible. The two-time World Cup champions had already secured their quarterfinal berth with commanding victories over Chile and Bolivia, establishing themselves as the tournament's most formidable force. Daniel Passarella's squad combined the tactical sophistication of European club football with the technical brilliance that had made Argentine football legendary. Gabriel Batistuta, their star striker, had terrorized defenses throughout the tournament, while the depth of their roster meant that even reserve players possessed the quality to dominate international matches. A tie would guarantee advancement, while even a one-goal defeat could suffice if the Americans managed to score. But such calculations felt academic when facing a team that had never lost to the United States in six previous encounters. The historical record was unambiguous: Argentina 5, United States 0, with one draw that felt more like charity than competitive football. For Sampson, the match represented the ultimate test of his coaching philosophy and his last chance to secure the permanent position he desperately wanted.

The coaching speculation that had dominated American soccer headlines for months reached its crescendo as the team prepared for Argentina. The United States Soccer Federation's preference for international experience remained unchanged, and Sampson's interim status felt increasingly precarious with each passing day. A comprehensive defeat to Argentina would provide the federation with the justification it was seeking, opening the door for another search for a foreign coach who could somehow transform American soccer into something it had never been.

"We have to play very assertively, very aggressively and be able to respond very quickly to whatever they throw at us," Sampson declared, his words carrying the weight of professional desperation. "We have to make sure that we are playing as a unit and providing a lot of support for one another because, technically, the Argentines are truly outstanding." Cobi Jones and Joe-Max Moore entered the starting lineup, replacing Mike Burns and Mike Sorber in a formation designed to provide more attacking threat. The changes represented Sampson's fundamental belief that American soccer could only succeed by embracing its natural athleticism and directness, even against opponents who possessed superior technical ability.

The capacity crowd at Estadio Artigas on July 14 anticipated a routine Argentine victory, with most of the 15,000 supporters draped in the sky blue and white that had become synonymous with South American football excellence. Argentina's decision to rest nine regular starters seemed to confirm the match's ceremonial nature—a warm-up exercise before the serious business of the quarterfinals began. But Passarella's rotation reflected confidence rather than complacency, as even Argentina's reserves possessed the pedigree to overwhelm most international teams.

The early minutes suggested that Argentina's tactical approach would prove successful. The Americans, still carrying the psychological burden of their defeat to Bolivia, struggled to establish any attacking rhythm. John Harkes' 25-yard shot in the opening minutes provided a brief moment of hope, but Carlos Bossio's save seemed to restore natural order. Argentina's immediate response was emphatic—Hugo Perez forcing a brilliant save from Kasey Keller before Gabriel Batistuta's rebound struck the post with the kind of precision that had made him one of world football's most feared strikers.

Rather than retreating into defensive shells when pressured, Sampson's team maintained their commitment to attacking football. The breakthrough came in the 21st minute through a sequence that embodied everything the coach had preached about American potential. Harkes' corner kick found the far post, where Cobi Jones' knockdown created the chaos that American soccer had learned to exploit. Frank Klopas, positioned perfectly fifteen yards from goal, drove the ball low into the right corner with a clinical finish. The goal silenced the Argentine supporters and transformed the match's entire dynamic. For the first time in the rivalry's history, the United States had drawn first blood against Argentina, and the psychological impact was immediate. Klopas, who had scored eleven goals in eighteen appearances for the national team, celebrated with the restraint of a player who understood the significance of the moment.

Eleven minutes later, the impossible became reality. Jones, playing with the freedom that Sampson's system had unleashed, beat his marker on the right wing and delivered a cross from the end line that found Lalas arriving at the perfect moment. The defender, who had been humiliated by Etcheverry just days earlier, tapped the ball under Bossio for a 2-0 lead that stunned everyone except the American players themselves. "I want your autograph, I want your autograph," the young Uruguayan fan had pleaded outside the Americans' hotel just hours earlier. Now, as Lalas celebrated his goal, it seemed that the entire South American football community was witnessing something unprecedented: the United States playing with the confidence and technical ability that had long been the exclusive domain of the continent's traditional powers.

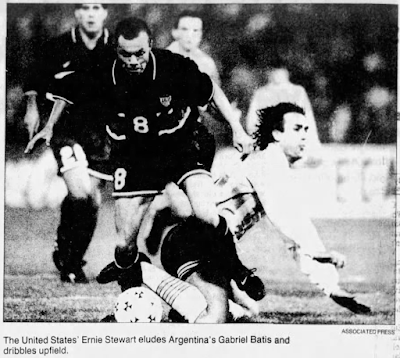

Argentina's response was predictable and desperate. Passarella abandoned his rotation strategy at halftime, introducing World Cup veterans Diego Simeone, Ariel Ortega and Abel Balbo in an attempt to salvage pride and avoid the humiliation of losing to a team they had never respected. The substitutions immediately shifted the match's momentum, as Argentina's superior technical ability began to assert itself. Wave after wave of attacks tested the American defense, with Burns making a goal-line save from Simeone's header that preserved the unlikely lead. But the United States possessed something that previous American teams had lacked: the mental toughness to withstand sustained pressure from world-class opposition.

The knockout blow came in the 59th minute, delivered with the kind of clinical efficiency that had become Sampson's trademark. Joe-Max Moore's pressing forced an Argentine mistake, and his slide tackle deflected the ball directly into Eric Wynalda's path. The striker's finish was simple—a tap into an empty net—but the goal's significance was profound. At 3-0, the United States had not only defeated Argentina but had done so with a margin that suggested dominance rather than fortune.

"They started nine different players, but look where those players are playing," Jones reflected afterward, his words carrying the weight of historic achievement. "Those nine players could start on any other national team in the world. And they started to panic when those nine players were getting whooped by us."

The final whistle unleashed celebrations that transcended sport. Paul Caligiuri, playing in his 100th international match, captured the moment's significance: "Today I was presented with the game ball and the first thought that came to my mind was that everybody on this team deserves to have that game ball because we played our hearts out. Everybody is a winner today."

For Sampson, the victory represented vindication of everything he had preached about American soccer's potential. The team that had been dismissed as pretenders had just defeated one of world football's most prestigious nations, and they had done so with a tactical maturity and technical ability that silenced every critic. "This has to rate as one of the biggest wins in U.S. soccer history," he declared, placing the triumph alongside the 1950 World Cup victory over England and the 1994 upset of Colombia.

The path to the quarterfinals had been secured in the most emphatic manner possible. The United States finished Group C with a 2-1-0 record, winning based on goal differential over Argentina and now, had earned the right to face Mexico—a team they had routed 4-0 just weeks earlier in the U.S. Cup—in a quarterfinal match that would determine whether this Copa América campaign could achieve something truly historic. It was only the second American victory on South American soil since 1930, and it had come against opposition that represented the pinnacle of the sport's development. The US had announced their arrival as a legitimate contender on the world stage, and they had done so with a performance that would be remembered as one of the greatest nights in American soccer history.

No comments:

Post a Comment