On This Day in 2005, the US Needed a Shootout in the Gold Cup Final to Secure Its Third Regional Title

The summer of 2005 found American soccer at a curious crossroads—ranked sixth in the world yet still seeking validation on its own continent. The CONCACAF Gold Cup, which took place that July, would provide that validation, but at a cost that would haunt Bruce Arena's preparations for the crucial World Cup qualifying matches ahead. What began as a showcase for American depth became a cautionary tale about the perils of tournament football, where victory and disaster often wear the same face.

Arena's squad had navigated the group stage with the methodical efficiency expected of continental favorites, though not without early warning signs. The opening match against Cuba in Seattle had nearly produced embarrassment—the Americans trailing 1-0 until Landon Donovan's late heroics salvaged a 4-1 victory that masked deeper concerns about the team's rhythm and focus. The Canada match followed a similar pattern: dominance in possession yielded minimal reward until Donovan's 90th-minute header finally broke the deadlock in a 2-0 win. Even the scoreless draw with Costa Rica, though sufficient to secure first place in the group, represented a psychological shift—the first time in 19 Gold Cup group matches that the Americans had failed to claim victory.

The knockout rounds revealed both the promise and fragility of Arena's tactical approach. DaMarcus Beasley's two-goal performance against Jamaica in the quarterfinals showcased the attacking fluidity that made the Americans a dangerous team. Still, the 3-1 scoreline obscured defensive vulnerabilities that would prove costly in the long run. By the time they faced Honduras in the semifinals, the Americans had already lost Conor Casey to a torn ACL and Frankie Hejduk to suspension, forcing Arena to rely increasingly on players with limited international experience.

The Honduras match crystallized all the problems with the tournament's trajectory. Arena's ejection in the 59th minute for arguing a call left his team rudderless at the worst possible moment, trailing 1-0 to opponents who had outplayed them for most of the evening. That John O'Brien and Oguchi Onyewu—the former struggling for form, the latter making just his seventh international appearance—provided the late goals that secured a 2-1 victory, spoke to both American resilience and the razor-thin margins that separated success from disaster. Arena's absence from the final was now guaranteed, adding another layer of disruption to a team already operating on fumes.

By July 24, when the Americans faced Panama at Giants Stadium, the toll of 18 days and six matches had transformed what should have been a celebration into an exercise in survival. The 31,018 fans who filled the stadium witnessed a team that bore little resemblance to the world's sixth-ranked side. Eddie Pope, Steve Cherundolo, Pablo Mastroeni, Steve Ralston, and Pat Noonan joined Casey on the injury list, forcing Glenn Myernick, Arena's assistant, to field a makeshift lineup that struggled to impose itself against Panama's determined challenge.

The match itself defied every expectation of American superiority. Where previous encounters with Panama had yielded comfortable victories—6-0 in October 2004, 3-0 just weeks earlier in Panama City—this final became a grinding test of wills between two exhausted teams. Panama, playing in their first Gold Cup final since 1993, discovered inspiration in the moment's magnitude. For 90 minutes of regulation and 30 minutes of extra time, neither team could find the breakthrough that would avoid the lottery of penalty kicks. Jimmy Conrad, Clint Dempsey, and DaMarcus Beasley had all squandered good chances for the Americans in the first half. At the same time, Luis Dely Valdes struck the post for Panama in the 75th minute and forced a diving save from Kasey Keller early in overtime. The scoreless draw felt like a fitting conclusion to a tournament that had steadily drained both teams of their creative energy.

When the final whistle brought the inevitability of penalties, the American bench revealed the physical and mental exhaustion that had defined their Gold Cup experience. Four players—veterans whose legs had carried them through nearly three weeks of competition—approached Myernick with the devastating admission that they simply could not take a penalty kick. Beasley, his hamstring too damaged to trust, withdrew from consideration in the 114th minute. The team that had begun the tournament with depth and confidence now faced its defining moment with a squad running on empty.

Santino Quaranta, showing the composure that would define his tournament breakthrough, volunteered to take the crucial first penalty. His successful conversion set the tone for what followed, as both Donovan and the unlikely hero Brad Davis found the net with their attempts. Davis, making just his second international appearance and fresh from entering as a substitute in the 84th minute, faced the ultimate test of nerve. His February 2004 penalty miss against Honduras in Olympic qualifying hung over the moment—redemption and disaster separated by the thickness of a penalty spot.

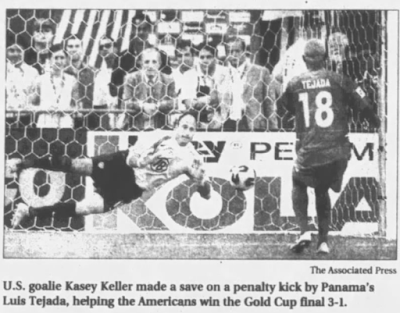

Keller's psychological gamesmanship proved equally crucial to the American cause. His dive to the left to stop Luis Tejada's opening penalty came from homework—the goalkeeper had noted Tejada's directional preference from Panama's quarterfinal victory over South Africa. When Felipe Baloy scored Panama's only successful penalty, it mattered little. Jorge Luis Dely Valdes struck the crossbar, Alberto Blanco sailed his attempt over the goal, and suddenly the Americans had won their third Gold Cup by the margin of 3-1 in the shootout.

The celebration that followed carried none of the euphoria typically associated with continental championships. Players limped toward each other rather than sprinted, their embrace speaking more to relief than joy. As they hoisted the trophy before the handful of fans who had remained through 120 minutes of scoreless football, the Americans understood that their victory had come at a price that might prove too steep for the challenges ahead. Arena's subdued reaction from the luxury box captured the tournament's essential contradiction—the Americans had proven their regional supremacy while simultaneously undermining their prospects for qualifying for the World Cup. The six injured players would miss the crucial Trinidad and Tobago match on August 17, forcing Arena to "rally the troops, get the Band-Aids out and try to get 11 guys on the field."

For Donovan, the tournament's leading figure despite his exhaustion, the Gold Cup had provided both validation and sobering perspective. "This could be the last time I ever win anything," he reflected, the weight of international football's harsh realities evident in his words. Davis spoke of redemption achieved—his penalty kick planted in the same spot where he had failed two years earlier, this time with the confidence born of necessity rather than hope.

The 2005 Gold Cup would be remembered not for the quality of its football or the drama of its conclusion, but for the questions it raised about tournament scheduling and player welfare. The Americans had proven they could win when everything went wrong, but at what cost? As Arena contemplated the roster he would need to assemble for World Cup qualifying, the Gold Cup trophy sitting in the Giants Stadium office served as both prize and burden—evidence of American resilience and a stark reminder of the price of continental glory in the modern game.