On This Day in 2013, Klinsmann's Blueprint Takes Shape With Gold Cup Triumph

The summer of 2013 found Jurgen Klinsmann's American project at a critical juncture—two years into his tenure as national team coach, the German's tactical revolution remained more theoretical than proven. Questions lingered with critics wondering whether his high-tempo, possession-based philosophy could produce the kind of sustained success that American soccer desperately needed. The CONCACAF Gold Cup would provide the testing ground, but not merely for another regional title. What unfolded over four weeks in July would either validate Klinsmann's vision or expose the limitations.

The tournament had begun with the kind of statement that Klinsmann had been demanding from his players since taking over from Bob Bradley. Against Belize in Portland, the Americans delivered a 6-1 masterclass that showcased both their depth and their newfound ruthlessness. Chris Wondolowski's hat trick provided the headlines. Still, it was Landon Donovan's milestone performance—becoming the first American to reach both 50 goals and 50 assists in international play—that captured the tournament's deeper narrative. Here was the veteran talisman, back from his controversial sabbatical, operating within Klinsmann's high-tempo system with the kind of precision that suggested his best years might still lie ahead.

The group stage continued to reveal both promise and persistent vulnerabilities in Klinsmann's approach. Cuba managed to score first against the Americans in Salt Lake City, exploiting the kind of defensive transition that had plagued the team in previous tournaments. Yet the response proved instructive. Donovan's penalty equalized before halftime, and then Corona and Wondolowski combined for three second-half goals that turned anxiety into emphatic victory. The 4-1 final score masked the early struggles.

The group finale against Costa Rica in Hartford provided the clearest glimpse of what Klinsmann was building toward. With first place already secured, the coach used the match to test his depth and tactical flexibility. Donovan's perfectly weighted pass found substitute Brek Shea in the 82nd minute, the Stoke City winger finishing clinically to secure both the 1-0 victory and the group's top seed. The goal represented everything Klinsmann valued—quick thinking, precise execution, and the kind of mental speed that separated good teams from great ones.

The knockout rounds transformed what had been an impressive run into something approaching domination. El Salvador arrived in Baltimore with a sellout crowd of over 70,000 supporters, creating the kind of hostile environment that had historically troubled American teams. Instead, the Americans silenced the partisan atmosphere with two early goals and never allowed their opponents to believe an upset was possible. The 5-1 victory extended their winning streak to nine matches and showcased the kind of clinical finishing that Klinsmann had been demanding from his forwards.

Honduras in the semifinals presented a different challenge entirely—a team that had already split two World Cup qualifiers with the Americans earlier that summer. For twenty-six minutes at Cowboys Stadium, the match followed a familiar script of American dominance without reward. Then Donovan took control of the tournament's defining moment, scoring twice in sixteen minutes to transform anxiety into celebration. The 3-1 victory sent the Americans to their fifth consecutive Gold Cup final, but more importantly, it validated Klinsmann's belief that his team could dominate possession while maintaining the clinical edge necessary to close out matches.

By the time Panama emerged from their semifinal upset of Mexico, the stage was set for a final that would determine whether American soccer had truly evolved under Klinsmann's guidance. The July 28 match itself unfolded with the kind of tactical tension that often defines continental finals. Panama, aware of their limitations against American possession, retreated into a compact defensive shape that prioritized organization over ambition. For sixty-eight minutes, the strategy proved frustratingly effective. The Americans dominated possession and territory but struggled to create the kind of clear chances that had characterized their earlier victories. Donovan, despite his tournament-leading statistics, found himself increasingly isolated as Panama's midfield congested the central areas where he preferred to operate.

Klinsmann's absence from the touchline—the result of his ejection in the Honduras semifinal—added another layer of uncertainty to the American cause. Watching from a luxury suite while assistants Andreas Herzog and Martin Vasquez managed the team, the suspended coach could only trust that his players had internalized the tactical principles he had spent two years installing. The moment of truth came when Shea entered the match in the 67th minute, bringing fresh legs to an attack that had been grinding against Panama's defensive discipline. Alejandro Bedoya's shot from outside the penalty area seemed destined for goalkeeper Jaime Penedo's gloves, but Donovan's perfectly timed run created chaos in the Panamanian defense. His attempt to connect with the ball—"I took a mighty swing at it and missed," he would later admit—proved to be the most effective dummy of his international career.

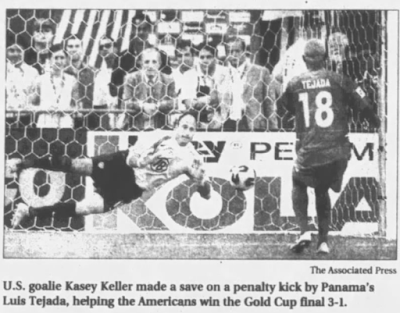

Penedo, deceived by Donovan's movement, committed to his left just as the ball deflected to his right. Shea, arriving with the timing of a player who had spent the entire tournament learning Klinsmann's system, needed only to guide the ball into the vacant net. The simplicity of the finish belied the complexity of its creation. The celebration that followed carried none of the manic energy typically associated with championship victories. The Americans' embrace seemed almost businesslike, the reaction of players who had come to expect success rather than hope for it. The eleven-game winning streak that the victory completed represented more than just a statistical achievement—it was evidence that Klinsmann's methods could produce the kind of sustained excellence necessary in Brazil the following summer.

For Donovan, the tournament had provided both personal vindication and a renewed sense of purpose. His five goals and seven assists earned him the Golden Ball as the competition's most valuable player. Still, more importantly, they demonstrated that his controversial sabbatical had not only refreshed but also strengthened his commitment to the national team. "This is not the end," he reflected after hoisting the trophy. "It's the end of the tournament, but hopefully this is just the beginning for a lot of us." The words carried the weight of a player who understood that Gold Cup success meant little without World Cup achievement, but they also suggested a renewed belief in the team's trajectory under Klinsmann's guidance.

The coach himself, despite his satisfaction with the victory, remained focused on the broader implications of what his team had accomplished. "We want to win in a way that you deserve it," Klinsmann observed, "and this was the best team in the Gold Cup." The comment reflected both pride in his players' development and awareness that CONCACAF competition, however valuable for building confidence and cohesion, represented only a stepping stone toward the global challenges that would define his tenure's ultimate success.

As the Americans departed Chicago with their fifth Gold Cup trophy, the tournament's true significance lay not in the silverware but in the blueprint it had provided for navigating the complexities of international competition. Klinsmann had inherited a team capable of regional dominance but limited by tactical predictability and mental fragility. The 2013 Gold Cup had produced a squad that combined American athleticism and determination with the kind of technical sophistication and tactical intelligence that could compete at the highest levels of world football. Whether that combination would prove sufficient for World Cup success remained to be seen, but the foundation had been unmistakably established in the summer heat of American stadiums.